The Role of Compliance Officers in HHS OIG Regulations

The role of compliance officers in HHS OIG regulations is to ensure policies and procedures are in place to mitigate the risk of a healthcare organization violating a law protecting HHS programs and beneficiaries from fraud or abuse. It is also the role of compliance officers in HHS OIG regulations to monitor compliance with the policies and procedures, and to enforce sanctions on workforce members when they fail to comply with the policies and procedures.

While this explanation of the role of compliance officers in HHS OIG regulations may sound complicated, it is not as difficult as it seems. There are usually only five healthcare regulations enforced by the Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) Office of Inspector General (OIG) – these being:

- The False Claims Act

- The Anti-Kickback Regulations

- The Physician Self-Referral Law

- The HHS OIG Exclusion Statute

- The Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA)

The False Claims Act

The False Claims Act protects HHS programs from being fraudulently charged for medical items or services. It is an offense to submit any claim that a healthcare organization knew or should have known was inaccurate; and, depending on the degree of intent, the penalties for violations of the False Claims Act can be civil (up to $27,894 per violation) or criminal (up to $250,000 per violation plus jail time for individuals and up to $500,000 per violation for organizations).

The role of compliance officers in HHS OIG regulations in this case is to ensure processes exist to verify the authenticity of reimbursement claims, that billing irregularities are flagged for investigation, and that security gaps are closed to prevent internal or external bad actors compromising HHS transactions. In the event that claims and billing are outsourced, the role of compliance officers is to conduct due diligence on third party service providers.

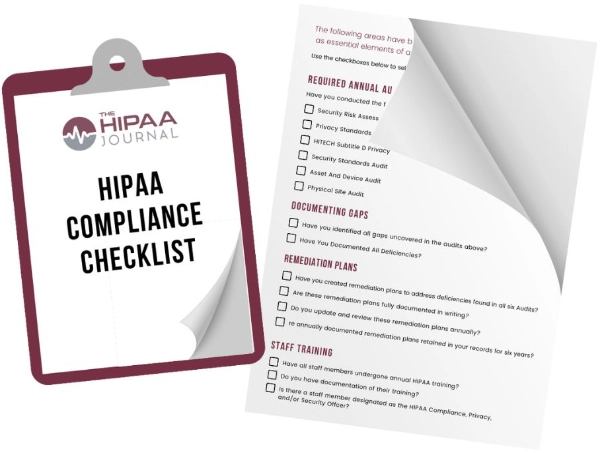

Get The FREE

HIPAA Compliance Checklist

Immediate Delivery of Checklist Link To Your Email Address

Please Enter Correct Email Address

Your Privacy Respected

HIPAA Journal Privacy Policy

The Anti-Kickback Regulations

The anti-kickback regulations exist to prevent inducements for referrals and “paid-for” recommendations for medical items or services. The consequences of “healthcare by inducement” are not only higher reimbursement claims, but also the risk that patients may not receive the most appropriate healthcare. Consequently, penalties for violations of the anti-kickback regulations are imposed on both the payer of an inducement and its recipient.

Because it is usually individuals who succumb to inducements, it is rare that an organization is investigated for an offense against the anti-kickback regulations. However, compliance officers need to be alert to individual members of the workforce accepting non-exempt inducements. This is because any induced reimbursement claims submitted via the organization will have to be repaid to HHS if a kickback allegation against a workforce member is proven.

The Physician Self-Referral Law

The Physician Self-Referral Law (aka The Stark Law ) prohibits healthcare providers from referring patients to “designated health services” when the healthcare provider or an immediate family member has a financial interest in the designated health service. To prevent violations of this law, compliance officers will need to know if any workforce members have business interests (including indirect family business interests) outside the healthcare organization.

However, when the HHS OIG investigates a violation of the Stark Law, the perpetrators are the referring healthcare provider (i.e., a member of the workforce) and the health service that benefitted from the self-referral. The organization for whom the compliance officer works will not be responsible for repaying the proceeds of any unlawful activity. Nevertheless, workforce members violating HHS OIG fraud laws is not something compliance officers want on their CVs!

The HHS OIG Exclusions List

In 1977, the Medicare-Medicaid Anti-Fraud and Abuse Amendments gave HHS OIG the authority to exclude individuals and entities from participating in HHS programs if they were found to have violated a healthcare fraud or abuse law. Depending on the violation, an exclusion can be mandatory (typically five years) or discretionary (no minimum or maximum limits) – during which time excluded individuals and entities cannot bill HHS programs directly or indirectly.

The role of compliance officers in HHS OIG regulations in this case is to ensure that no excluded individual becomes a member of the workforce and that no goods or services are supplied by an excluded entity. Healthcare organizations that employ excluded individuals or who contract goods or services from an excluded entity can be fined up to $20,000 for each good or service unlawfully claimed plus three times the amount claimed from an HHS program.

The Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA)

EMTALA requires qualifying healthcare organizations that participate in HHS programs to examine an individual requesting emergency care and provide emergency treatment regardless of the individual’s insurance coverage or ability to pay. If the healthcare organization cannot provide appropriate emergency treatment, they must stabilize the individual and arrange a transfer to another healthcare organization that has appropriate treatment capabilities.

Qualifying healthcare organizations that fail to examine an individual or who fail to accept an individual transferred from another healthcare organization can be fined up to $129,233 and added to the HHS OIG Exclusions List. What can complicate the role of compliance officers in HHS OIG regulations such as EMTALA is when exemptions exist depending on location, the nature of the emergency treatment required, and the professional affiliation of healthcare workers.

How to Fulfil the Role of Compliance Officers in HHS OIG Regulations

The way to fulfil the role of compliance officers in HHS OIG regulations is to adapt existing policies and procedures to mitigate the risk of violating a healthcare fraud or abuse law. For example, most healthcare organizations are required to audit their claims and billing processes as a condition of participation in Medicare and Medicaid. Existing procedures could be adapted so that reimbursement claims are verified and irregularities are flagged in the audit process.

Similarly, with regards to conducting due diligence on third party service providers, this is a condition of HIPAA compliance when PHI is shared with a business associate – as are reasonable and appropriate measures to protect the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of electronic PHI whether it is shared with a business associate or processed inhouse. Complying with HIPAA Security Rule automatically ensures that Part 162 transactions are more secure.

With regards to identifying violations of the anti-kickback regulations, induced reimbursement claims should be flagged as part of an effective audit process, while the requirement to check individuals against the HHS OIG Exclusions List is an extra check to add to the existing Level 2 checks many healthcare organizations already have to do before engaging a new member of the workforce in order to comply with state employment laws.

As many of the policies and procedures required to fulfil the role of compliance officers in HHS OIG regulations are adaptions or extensions of existing policies and procedures, monitoring workforce compliance with the policies and procedures should not create an additional compliance burden – nor should enforcing sanctions on workforce members when they fail to comply with the policies and procedures. Nonetheless, compliance officers uncertain about how to fulfil their role with regards to HHS OIG regulations should seek independent compliance advice.